Interview with Kim Schneiderman, LCSW on the Concept of Self

I would like to know about your career, and how you got started, and interested in psychology?

I suppose you could say my interest in psychology began in college as an English

major. I was drawn to the psychology of the characters in literature, and how they

evolved over the course of their storylines. It wasn’t until I had an identity crisis after

graduating from college and moving out to San Francisco in my 20s, that I became

interested in my psyche and personal evolution. Between social, work and family

stressors, and a spiritual awakening sparked by exposure to a variety of lifestyles and

ideas, I became increasingly preoccupied with the meaning of life, and my own unique

path. Overwhelmed, I needed sorting my thoughts and managing my emotions, which

felt like unwanted alien life forms trying to take over my body. So I entered therapy in

hopes of understanding these creatures, and being able to hear my own voice amid the

noise of competing voices offering suggestions or examples of how to be. Therapy was

somewhat of a revelation. As I began to explore my psyche, I became fascinated with

the mysterious ways of the mind and began reading psychology books. Eventually, I

returned east and enrolled in a social work master’s degree program. Today, I continue

to be engaged in my own psychotherapy to understand myself better so I can bring

greater compassion and understanding to my practice with clients.

What areas of psychology interest you the most, and why?

Generally speaking, I gravitate towards more holistic, transcendental and existential

schools of psychology that honor the connection between mind, body, and spirit, and

regard human struggles as opportunities to deepen in compassion, love and

awareness. I’m especially drawn to the works of Carl Jung, Joseph Campbell, and

Victor Frankel. More specifically, I’m drawn to Jung’s idea of a collective unconscious

that is shared by all humanity and expresses itself in myths, archetypal symbols, and

dreams that once understood and decoded, can help a person heal deep wounds and

experience more connectedness to the human story. Similarly, I’m drawn to Frankel’s

idea that human nature is motivated by a search for life purpose, and Campbell’s

concept that we are all on a heroic journey of sorts, that once undertaken, transform us

into deeper, more fully expressed versions of ourselves. All this is why I often liken

myself to a psycho-spiritual midwife of sorts, helping people navigate the narrow bridge

of difficult life transitions and give birth to their authentic self.

In recent years, I’ve become interested in more body-centered psychotherapies. These

schools hold that our emotional and mental puzzles can’t be analyzed and solved like

geometry problems. But rather, the human body possesses an intrinsic wisdom of its

own that reveals itself when one is able to relax, be curious, and listen deeply.

Specifically, I’ve grown tremendously because of my own involvement with Focusing,

Gene Gendlin’s concept that your body can “sum up” the whole way you feel about

something you’re going through, into a single yet complex felt sense. That felt sense

actually contains both the problem and the way forward, but for it to reveal itself, it

needs a bit of patience and acceptance. Working with clients in therapy means helping

them stay attuned to a fuzzy bodily felt sense until it becomes clear and reveals

meaning. My adventures in Focusing led me to Internal Family Systems (IFS), another

body-centered model that perceives problematic behaviors as the self being hijacked by

protective parts of ourselves that guard the more vulnerable, exiled younger parts that

hold all our pain. These parts can be explored and healed through deep body listening

and open-hearted dialogue and inquiry. More on IFS to follow.

What is the self, can it get lost, and how do we know when we are being true to

ourselves?

Since ancient times, philosophers have wrestled with the definition of self. Aristotle

describes the self as a core essence of a living being that is defined by how it functions

in the world. Eastern traditions equate the self as an egotistical state which must be

transcended to experience unity with nature and divine consciousness. Freud conceived

the self as consisting of three parts – an id, a primitive, disorganized part of the brain

that contains basic, instinctual drives, the superego, a self-critical conscience that

internalizes cultural norms, and the ego, which shapes our identity as it mediates

between the two other states.

However, one of my favorite conceptualizations comes from Internal Family

Systems, a therapeutic modality created by Richard Schwartz. Here, the self is

presented as the conductor of an orchestra of sub-personalities, or “parts” – for

example, a striving part, a worrying part, an exiled childlike part that holds all our pain.

The conductor serves as an inner resource of wisdom, embodying the divine-like virtues

of compassion, curiosity, calm, creativity, courage and confidence. When we are self-

led, we respond to life with these qualities, mindfully leveraging the appropriate parts to

collaboratively play the called-for notes in various situations.

According to the IFS definition, the self never actually gets lost. It just gets

overtaken by sub-personalities that take on extreme roles – for example, a highly critical

part, an unforgiving taskmaster part, a raging part, an alcohol-binging part – to protect

our most vulnerable, wounded parts, which become exiled in our bodies holding all our

pain. These exiled parts develop in childhood when the self, in its natural state, is

overtly or tacitly rejected, shamed, or criticized. Although they hide from our awareness,

we can sense them whenever something triggers a strong emotional reaction. Once

triggered, protective parts step in to protect the exile, either by controlling a situation, or

distracting us because they fear we can’t handle the emotional intensity of our old

wounds. As various parts mobilize to protect the exile from overwhelming the self, the

self essentially “gets lost.”

One reason for the coup-de- parts is inadequate parental mirroring in childhood,

resulting in a diminished sense of self. As widely observed, children are virtual sponges

for feedback about who they are and what t hey are good at. Especially during earlier

stages of development, children look to parents and caregivers to reflect back their

talents, feelings, thoughts and uniqueness. Eye contact, presence, interest and curiosity

instill in the child a curiosity about themselves and a sense of worth. Parents who

respond to their children with self-led qualities like curiosity and compassion

communicate acceptance, acknowledgement, and worthiness, helping a growing child

develop the necessary self-trust muscles that support confidence and self esteem.

When parents are distracted or disinterested, children don’t get enough positive

feedback that they are OK, loveable and can trust the self. Conversely, when parents

are over-bearing and led, for example, by parts that are preoccupied with appearance or

status, their excessive concern over how their children define themselves in the world

provides few opportunities for the child to self-reflect and have his or her own positive

thoughts and feelings. Consequently, the child will exile those parts that are deemed

unwelcome by the outside world, and develop protective parts that help them get the

love and attention they seek.

The danger, of course, is that in both instances, these protective parts disconnect

the child from his or her self, compromising self esteem and positive energy. Hence,

the child who naturally would be inspired to become an artist born into a family that

rejects creativity in favor of science, math, and business savvy, exiles his unwelcome

creative self, and feels lost and unfulfilled in medical school.

We know we are being true to ourselves when we take actions, make decisions, or

speak from a place of of curiosity, calmness, creativity, courage, or compassion instead

of fear, anger, pride, shame, guilt and other protective emotional parts.

In this day, and age of social media, its really hard to have a sense of self, how do we put ourselves in balance, and ignore all of that?

During orientation of my first social work job, I participated in a group exercise

that became a guiding metaphor about to remain connected to myself amid all the noisy

distractions. I was blindfolded and instructed to walk from one end of a large room to the

other, without stepping on any napkins (“landmines”) that had been scattered across the

floor. To make my way, I would have to hone in on the voice of a single colleague, who

would stand on the opposite side of a large room and yell instructions on how to

navigate the napkin obstacle course. Meanwhile, the rest of my colleagues would be

yelling at the top of their voices, sending all kinds of mixed messages about where to

step, including on the landmines. As I recall, it was a fun but difficult exercise, and I

barely made it across.

Sometimes life can feel that way – it’s as if we are wandering through the

darkness, unsure of which direction to go, guided only by our intuition that speaks to us

in a still quiet voice while distractions thunder around us. Fortunately, there are many

ways to tune into the self including contemplative practices like meditation, creativity,

connecting to nature, intimate relationships, and engaging in self inquiry practices like

psychotherapy. It’s not surprising, that as the number of digital distractions has

intensified, so has the density of yoga and meditation studios per capita. It’s as if society

has intuitively offered an antidote to its own self-generated malady of over-stimulation.

You mention creativity as being a outlet being your authentic self, how do we remain

positive, and focus on that while having pressure from everyone around us?

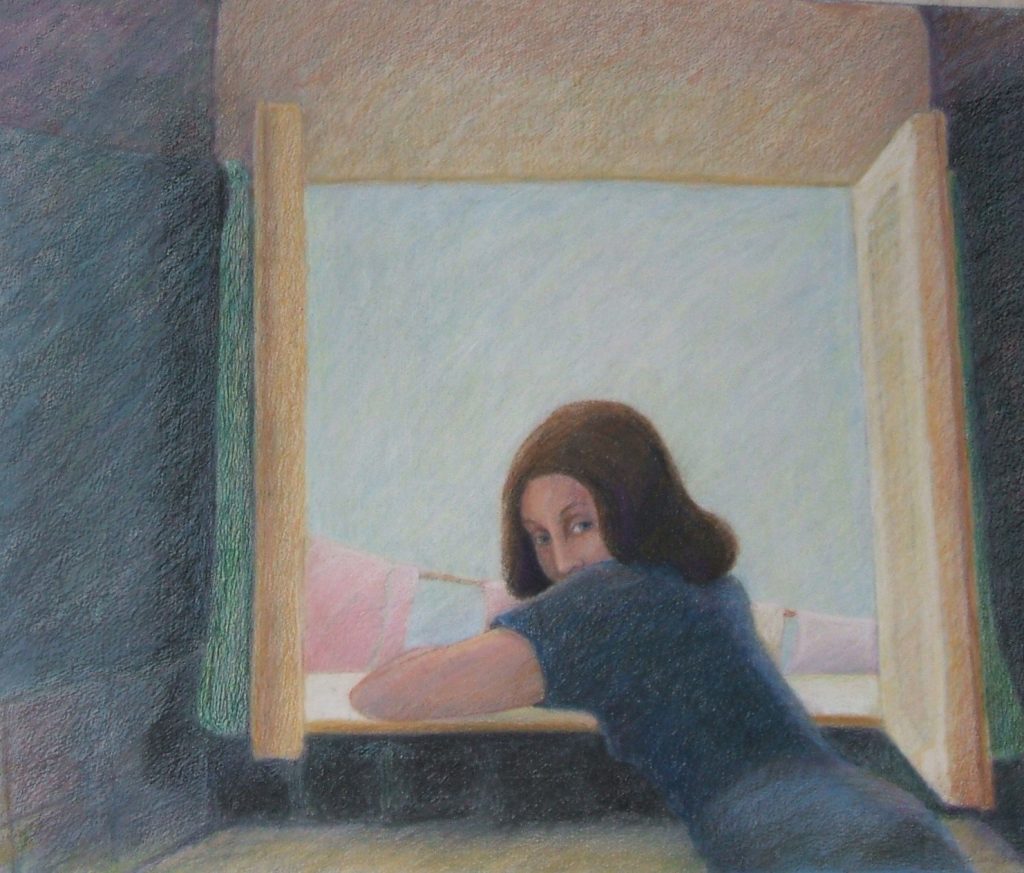

On a simple level, engaging in creative acts help us reconnect with more enduring,

divine-like qualities of the self. After all, the self is naturally creative. The poem we write,

the picture we paint, the music we perform, the photograph we take, the dance we

express, becomes a mirror of our inner world, reflecting back the self quality of creativity

that might otherwise get drowned in a cacophony of noisy exiled and protective parts.

This also explains why self expression can be so anxiety provoking – part of us

may seek the buried treasure submerged in our psychic depths, while another part of us

may fear dredging up monsters.

That’s why creativity also calls upon another aspect of the self – courage. As

psychologist and creativity guru Rolly May points out in this signature work, “Courage to

Create,” the creative act is the outcome (synthesis) of various dialectics (conflicts,

contradictions, and tensions).” In other words, creativity becomes a means of allowing

our inner conductor, the self, to dialogue with, and resolve and reflect the tensions

between, our various parts.

Thus, creative expression become a corrective lens, allowing us to catch glimpses

of what is normally out of sight, including our own divine natures. Once we behold our

creation – the painting, the film, the poem, the ballad – we can’t help but know, and

maybe even appreciate, the conductor and our inner orchestra just a little bit better.

Looking in this mirror, we see perhaps that we are the sum of our parts, but also so

much more.

How do you stop allowing negative perceptions of yourself influence how you feel about yourself?

The self-help industry has built an empire around this topic. The Internal Family

Systems model considers inner critics as parts of yourself that are trying to protect you,

but doing it the wrong way. For example, the inner critic may be trying to make sure that

you stay ahead of external criticism and avoid rejection and abandonment. This may be

the result of early childhood experiences where you learned that to be loved, you had to

get perfect grades or always look beautiful. Once you understand the inner critic is

trying to protect you, you can dialogue with it, showing it all the ways you are loved and

supported just for being yourself.

Another technique is to view your life as a work in progress and see yourself as

an ever-evolving character in a personal growth adventure. As I write in my book, “Step

Out of Your Story: Writing Exercises to Reframe and Transform Your Life” (New World

Library, 2015), every life is an unfolding story, a dynamic, unique, purposeful, and

potentially heroic story that is open to interpretation, especially your own. How we

“read,” or rather interpret, our story affects how we feel about ourselves, which can

influence how our lives unfold. Whether you consider yourself a heroic figure

overcoming obstacles or a tragic victim of destiny often depends on how much you

value your own character development. For example, seeing a failed relationship as a

lesson in intimacy, resilience, and humility will make us feel a whole lot better, and

emotionally ready for our next relationship, than shaping the story as evidence of

personal worthlessness. In other words, instead of focusing on what’s wrong with you,

look for opportunities to learn and grow from situations.

What influences who we turn out to be a person? Are we always going to be bits, and pieces of other people? Or can we ever really truly be our own?

The simple answer is: everything and everyone. After all, we don’t live in a vacuum. As

children, our caregivers influence have the greatest influence on how we perceive

ourselves and the world around us. But we also pick up messages about acceptable

and unacceptable behavior from our parents, siblings, peers, teachers, and the culture

at large. So ultimately, we are one self with multiple parts whose goal is integration and

individuation. Carl Jung defined individuation as a life-long process in which the self,

through adventures in living, continually clarifies and articulates itself. In other words,

we’re given the raw ingredients from our surroundings, but we create and refine the

recipe of self over a lifetime, often by tasting different experiences.

Credit:

Interview conducted by: Danya Halsalem

You can connect with Dr. Kim Schneiderman, LCSW here: Stepoutofyourstory.com

Responses