5 Harmful Myths About Mental Illnesses

In 1961, Thomas Szasz published The Myth of Mental Illness, a book that discussed his belief that mental illnesses were unnecessary diagnoses used to excuse the behavior of moral and socially deficient people. While there are still some people who hold this view, the majority of the public have a much better understanding of mental illnesses. However, there are still some common myths we can’t seem to get away from that can have harmful effects on the treatment of those with psychological conditions.

1.) People with mental disorders are likely to be violent.

A front page article in The Sun, a newspaper in the United Kingdom, released the shocking information that over 1,200 people had been killed by persons with mental illnesses in the past ten years in England. This statistic was actually true. The problem: they were including suicides, which accounted for almost 97% of the total deaths. In all actuality, the rates of violence or criminal behavior in people with mental illnesses is very small, with the majority of instances occurring with substance abuse disorders and those with previous histories of violent behavior. In fact, people with a psychological condition are more likely to be the victims of criminal and violent behavior. They’re more likely to experience domestic violence and sexual abuse, and they’re also more likely to suffer an intense psychological reaction to being victimized (The Lancet).

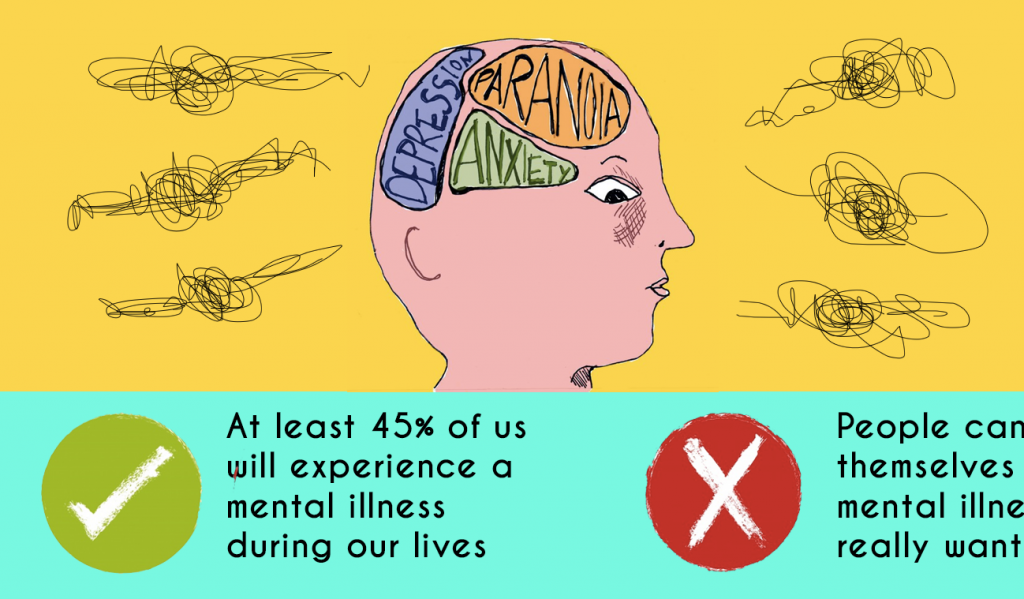

2.) People can pull themselves out of a mental illness if they really want to.

Probably one of the most popular myths about mental illnesses, especially when it comes to depression and anxiety, is the person is just oversensitive and could easily fix the problem. This is where the phrases “they just want attention,” and “they like feeling miserable,” comes into play. First of all, mental disorders often have genetic factors that influence predisposition and chemical imbalances that can’t be influenced by sheer willpower. Thinking the person suffering from the condition is voluntary and caused by some inherent weakness can cause the person to be less likely to seek some sort of treatment for the condition or even to discuss their struggle in general, which is extremely harmful to the process of recovery. Secondly, it is very hard to make the first step in getting help. From personal experience, the process of getting professional help is daunting task. First, you have to work up the courage to even admit to yourself there is a serious problem, then there’s trying to find a therapist nearby that is accepting new clients and works with your insurance. After that, it’s a trial and error process of therapy techniques and medications that can take a considerable amount of time. Some people choose to handle the problem on their own, which is entirely their decision—there is absolutely no benefit to either pressuring someone to go to therapy or telling them to just get over it. Dealing with a mental illness can be scary, emotionally draining, and exhausting, making every ounce of support crucial for the person you love to get the care they need. That being said….

3.) Love and support are the absolute cures to mental illness.

Every therapist and doctor will tell you that social support is a very important factor when it comes to the recovery process, but it is not the sure fire way to fix someone’s mental illness. We’ve all seen movies where a child with a serious behavioral problem or a girl who suffers from emotional outbursts is made completely better by the end of the movie because someone went out of their way to inspire a sudden realization that they can be loved. However, if you expect this to happen in real life, you’re probably going to be thoroughly disappointed. Key features of several mental illnesses include social isolation and constant fear of rejection. While showing someone you still care about them and are willing to stay beside them through their struggle is strongly encouraged, people who suffer from a mental illness may have a hard time believing those actions in the first place, much less showing some sort of appreciation for them. Expecting significant progress from displays of affection and encouragement may make it harder to keep showing the same level of support when the person has a particularly bad day or relapse into unhealthy habits (Butler & Hyler, 2005).

4.) Having a mental illness is a social death sentence.

As mentioned above, there are still some stigmas about mental disorders that are a bit unsettling. However, it’s important to note that the overall tone of the reception of those who struggle with some type of psychological condition is shifting towards a more positive one. The awareness of mental illnesses and what causes them has more than doubled since the 1950’s (Link, Phelon, Bresnahan, Stueve, Prescosolido, 1999). With the spreading knowledge of genetic predispositions and chemical imbalances, mental disorders have started to carry a sense of blamelessness, making them more “acceptable” than physical illnesses in some cases. Some even see having a mental illness as a sign of a greater understanding of what it means to be human (Martinez, Mendoza-Denton, and Hinshaw, 2011.) It doesn’t take a thorough knowledge of the DSM to cause someone to be aware of the aspects of certain mental illnesses either. Ardila-Gomez et al (2014) found that even living near a place that offers mental health services can raise the rates of acceptance and understanding from 21% to over 80% of the population.

5.) You will become your label.

This is a big fear whenever it comes to making the decision to go to a mental health professional. Instead of a person, they become a borderline, a manic-depressive, an anorexic, a schizophrenic, the list goes on and on. With this comes the feeling that whatever mental illness is present becomes the entirety of who the person is; the disorder has completely taken over. I could write pages and pages about the benefits of Rogerian-based therapy, but the basic idea is there cannot be any sort of success out of a therapy session where the client ends up feeling like they aren’t seen and valued as a person. Rogerian therapists have a big push for person-first terminology. For example, instead of “an autistic child,” use “a child with autism.” This puts the emphasis on the person, not the illness. Some researchers have even debated if telling clients their official diagnosis is even beneficial to the recovery process, stating that in all honesty, labels are more for insurance purposes (Martinez et al, 2011). Some people feel better if they have a term for their experience, but it isn’t necessary in all cases. The bottom line is every mental illness exists on a spectrum. Each person experiences them differently, and if a client feels the mental disorder itself is the only thing his/her therapist or doctor is focused on, it’s highly recommended they find a new one.

References

Ardila-Gómez, S., Ares-Lavalle, G., Fernández, M., Hartfiel, M. I., Borelli, M., Canales, V., & Stolkiner, A. (2014). Social perceptions about community life with people with mental illness: Study of a discharge program in buenos aires province, argentina.Community Mental Health Journal, doi:10.1007/s10597-014-9753-4

Butler, J. R., & Hyler, S. E. (2005). Hollywood Portrayals of Child and Adolescent Mental Health Treatment: Implications for Clinical Practice. Child And Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics Of North America, 14(3), 509-522. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2005.02.012

Link, B. G., Phelan, J.C., Bresnaham, M., Stueve, A., & Pescosolido, B. A. (1999). Public Concepts of Mental Illness: Labels, Causes, Dangerousness, and Social Distance. Am J Public Health, 89(9), 1328-1333.

Martinez, A. G., Piff, P. K., Mendoza-Denton, R., & Hinshaw, S. P. (2011). The power of a label: Mental illness diagnoses, ascribed humanity, and social rejection. Journal Of Social And Clinical Psychology, 30(1), 1-23. doi:10.1521/jscp.2011.30.1.1

Truth versus myth on mental illness, suicide, and crime. (2013). The Lancet, 382(9901), 1309. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62125-X

Image

Slogan. Rethink Mental Illness. SA Health. Retrieved from sahealth.sa.gov.au

If you have any questions about this list or want to contribute articles for us, email psych2go@Outlook.com.

Responses