8 Warning Signs Of A Mental Illness

Writer’s note : Disclaimer, dearest readers! This article is not meant for diagnosis or treatment. It is merely for informative purposes and to raise awareness among the general public. If you or someone you know have such struggles, we strongly urge you to seek professional help from a Psychiatrist or other trusted mental health professionals.

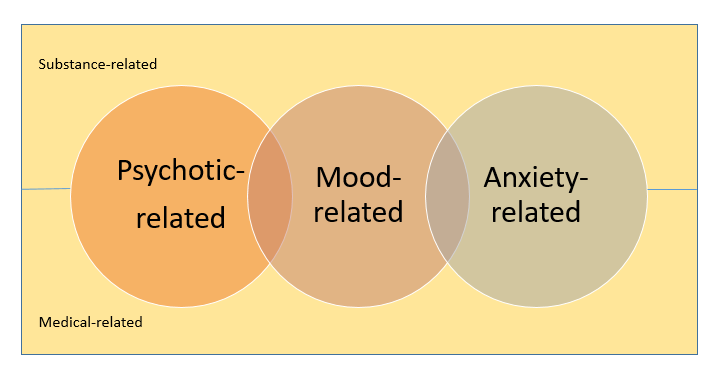

A trained mental health professional would diagnose a psychiatric illness based on the guidebook, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5). The psychiatric illnesses would fall under two groups; based on the pathology or the syndrome (a collection of symptoms or signs) appear in the patient. Majority of psychiatric illnesses fall under the category of syndrome. They are diseases related to the brain function rather than the structure of the brain.

Above (Figure 1) is the summary of the listed Psychiatric illnesses as stated in DSM-5. Some illnesses have purely mood-related symptoms, whereas there are those with overlapping mood-related and psychotic-related symptoms. For example, major depressive disorder (MDD) is purely mood-related, however MDD with psychosis consists of a combination of psychotic and mood-related symptoms.

Major mental illnesses such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder rarely appear “out of the blue.” Most often family, friends, teachers, or individuals themselves recognize that “something’s not quite right” about their thinking, feelings, or behaviour before one of these illnesses appears in its full blown form.

Being informed about developing symptoms, or early warning signs, can lead to intervention that can help reduce the severity of an illness. It may even be possible to delay or prevent a major mental illness altogether (American Psychiatric Association, n.d.). Now, let’s look at what are the 8 warning signs of a mental illness, shall we?

- Recent social withdrawal and loss of interest in others

Tomoki (not real name), quitted his job in 2015. He was determined to get back into work and regularly visited the job centre. He also attended a religious group almost daily, but the group’s leader started publicly criticising his attitude and inability to get back into work. When he stopped attending, the leader called him several times a week and the pressure, combined with that from his family, eventually caused him to withdraw completely. Consequently, he blamed himself, didn’t want to see anyone and didn’t want to go outside.

Social withdrawal is defined as the lack of social relations with one’s family and friends. Barzeva et al. (2019) in line with Rubin et al. (2009) report that it is “an umbrella term referring to an individual’s voluntary self-isolation from familiar and/or unfamiliar others through the consistent display of solitary behaviours such as shyness, spending excessive time alone, and avoiding peer interaction.”

Hikikomori, is a term coined by a psychiatrist, Saito, based on the phenomenon of well-known social withdrawal in Japan (Saito, 1998; Saito, 2010). Hikikomori is withdrawing from contact with family, having almost no friends, and not attending school for adolescents. Since the late 1970s, this has been a silent epidemic among teens and young adults in Japan. Recently, Japanese scholars discern the phenomenon of Hikikomori from social withdrawal as being as a consequence of a psychiatric psychopathology that occurs together with the diagnosis of depression, personality disorder, anxiety disorder, etc. Social withdrawal and the difficulty in creating social relationships do not manifest themselves as a primary symptom but do not meet the criteria of a diagnostic labels so far theorized by international psychiatry (Suwa, 2013). To overcome this diagnostic gap, the Japanese Ministry of Health created guidelines in 2003 to help identify the Hikikomori phenomenon, by establishing the presence of certain criteria:

- Home-confined lifestyle

- Lack of motivation to attend school or work

- Absence of criteria for other psychiatric diagnoses such as agoraphobia, schizophrenia, etc

- Duration of symptoms more than 6 months

According to Morese et al. (2019), working with secluded adolescents has revealed that their families should be included in the therapeutic relationship. It has been also detected that the characteristics found in the secluded adolescents can be traced back to relationships within the family. For example, there is often an intense mother/child relationship that promotes dependence and obstacle in the natural processes of separation and individuation, a distant or absent paternal figure who initially idealizes and places numerous expectations in the child and when that happens, when these expectations are not satisfied, it becomes degrading.

2. An unusual drop in functioning, especially at school or work

Your student, Lizzie, 16 years old, always obtains an A in her Additional Mathematics subject. However, during one semester examination, you notice that her grade drastically falls down to a D. You also notice that she always appears sleepy in class. You also get to know from the other teachers that Lizzie’s mother has recently got married to a new guy. So, currently Lizzie has a stepfather.

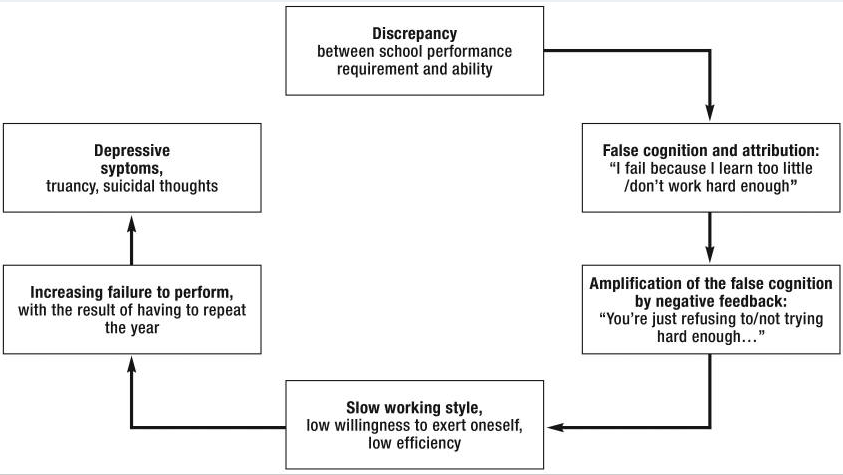

Worldwide, the prevalence of depressive disorders in childhood and adolescence is 4–5% (Costello, Egger & Angold, 2005). Girls are affected twice as often as boys (Hyde, Mezulis & Abramson, 2008). The main symptoms include difficulties in concentrating, lack of self-worth, low mood, joylessness, a loss of activities and interests, social withdrawal, giving up leisure activities, changes in appetite, sleep disruption, and—in moderate to severe forms—suicidal thoughts and acts.

Figure 2 summarizes the cycle experiences by the students. Affected students experience their inability to perform as a personal failure, and having to repeat a year is interpreted as punishment, which triggers additional stress. Because of their depression, such students cannot compensate for the learning impairment. This cycle is amplified by the fact that adolescents are less likely to seek help (Algaier et al., 2011); consequently, support and relief regarding their school-related demands mostly comes too late for those affected.

What are the appropriate solutions for this issue? According to a German psychiatrist sub specializing in child and adolescent psychiatry, Prof. Dr. med. Gerd Schulte-Körne (2016),

- Children, adolescents, and their families should be informed about the options available in the healthcare system, and access to such services should be improved.

- The school as a central institution in the education system, with its support systems in the psychosocial area (school social workers, school psychologists) can take a central role in this

- Establish a cooperation with services provided by the healthcare system (public health services; general practitioners; outpatient, part-inpatient, and inpatient child and adolescent psychiatric and psychosomatic services, as well as psychotherapeutic and medical services for children and adolescents) and by youth welfare services, by implementing the following measures: Screenings, Preventive measures, Changes in class and school climate, Advanced training for teachers.

3. Problems with concentration, memory, or logical thought and speech that are hard to explain

You are watching a movie in the movie theatre with your best friend from your school. However, you find it hard to concentrate on the plot of the movie, your attention span is like that of a goldfish. After the movie ends, your best friend asks you what you think about a certain scene in the movie, however, you are unable to recall the particular scene.

What does unable to concentrate mean?

According to an article written by Rachel Nall and medically reviewed by Dr. Alana Biggers (2019), all of us rely on concentration to get through work or school every day. When you’re unable to concentrate, you can’t think clearly, focus on a task, or maintain your attention.

Your performance at work or school could be affected if you can’t concentrate. You may also find that you can’t think as well, which can affect your decision-making. A number of medical conditions may contribute to or cause inability to concentrate. It’s not always a medical emergency, but being unable to concentrate can mean you need medical attention (Nall & Biggers, 2019).

Being unable to concentrate affects people differently (Biggers & Nall, 2019). Some symptoms you may experience include:

- Being unable to remember things that occurred a short time ago

- Difficulty sitting still

- Difficulty thinking clearly

- Frequently losing things or difficulty remembering where things are

- Inability to make decisions

- Inability to perform complicated tasks

- Lack of focus

- Lacking physical or mental energy to concentrate

- Making careless mistakes

When do you need to seek medical help for being unable to concentrate?

Seek immediate medical attention if you experience any of the following symptoms in addition to being unable to concentrate (Biggers & Nall, 2019):

- loss of consciousness

- numbness or tingling on one side of your body

- severe chest pain

- severe headache

- sudden, unexplained memory loss

- unawareness of where you are

Make an appointment to see your doctor if you experience the following symptoms:

- affected memory that’s worse than usual

- decreased performance in work or school

- difficulty sleeping

- unusual feelings of tiredness

- If being unable to concentrate affects your abilities to go through daily life or enjoy your life.

4. Loss of initiative or desire to participate in any activity; apathy

You are living with your sister. Since the pandemic, her employer has instructed her to work from home. However, since then, you notice the changes in her behaviour. She no longer likes to dress elegantly while going out, and she becomes lazier in doing her daily aerobic exercise.

According to a licensed psychotherapist, Dr. Barton Goldsmith, Ph.D., LMFT (2021), anhedonia, located somewhere between sadness (when your life isn’t going the way you want it to) and depression (when you can’t get out of bed). It can refer to the inability to feel pleasure, can manifest as a reduced desire and reduced motivation to engage in activities that were once pleasurable. We all want to feel good, but people who suffer from anhedonia just can’t, and that makes their depression worse.

If you live in a place where winter snow or just a lot of rain makes life dreary, your anhedonia may be driven by seasonal affective disorder (SAD). Letting in some warmth and light could increase your willingness to take in a tiny bit of joy. I like it when I see the sun shining off the water, and I have learned to take it in when I see it. That may be the first step in beating this silent scene-stealer into submission.

This is different from the struggle to find joy in our current pandemic world, COVID has created depression and anxiety all its own: coronaphobia. Pandemic isolation actually might not be affecting people with anhedonia as much as those who have been very socially and creatively engaged. Unfortunately, with anhedonia, even the thought of getting the vaccine, seeing family, and going out again brings no pleasure. If you are feeling down in the pandemic, you have to forget about what’s normal and look for the new. Life may not be like it used to be or, more accurately, how we want it to be for a very long time, if ever.

It’s necessary to start with the little things. Just be willing to let in a little bit of the good. You don’t need to even feel it at first, but it will help to start noticing things that you remember you used to think were nice, like sunsets, fresh food, and flowers, cooking, and eating. All those little moments add up and become powerful enough to make you want to feel the joy more. Give it a chance. The way you feel won’t change overnight, but it will change, and you will feel better (Goldsmith, 2021).

5. A vague feeling of being disconnected from oneself or one’s surroundings; a sense of unreality

Can you imagine…feeling like everyone you know, everything around you, everything you are thinking and feeling are fake. Imagine that your senses, informing you of what is currently happening in your first-person experience, can’t be trusted. Imagine that instead of being in the here-and-now, you feel like a detached observer, watching yourself from a disconnected vantage point with no possible way to reconnect yourself to reality (Bates, LMHC, LMC, LPC, NCC, 2019).

No, this isn’t the plot of Christopher Nolan’s movie Inception. This is a real phenomenon that people deal with every day. And before you start thinking the experience sounds kind of cool, I can assure you, it’s not.

Clinical terms used to describe this experience are:

- Depersonalization — An internal feeling of disconnection from oneself, i.e., self-estrangement.

- Derealization — An external feeling of disconnection from one’s surroundings.

- Dissociation — Detachment from one’s physical and emotional experience.

Collectively, these three terms are known as DDD.

So, what can you do if you suffer from DDD? Is there hope?

Yes, there is hope. According to Dan Bates, LMHC, LPC, NCC (2019), there are some suggestions to help you cope with DDD:

- Seek professional support

- Mindfulness: Mindfulness is the ability to make observations of oneself without judgment. The point of this is to make first-person observations. For example, notice what is going on in your body:

-Notice your breath and the sensation of your lungs filling with air

-Notice any focal points of discomfort in your body

-Notice any body sensations, such as increased heart rate, flushed face, or muscle tension

- Stay calm : Try regulating your nervous system by:

-Regulating your breathing by taking slow, deep breaths

– Practicing progressive muscle relaxation

- Acceptance: Fighting against DDD actually gives DDD energy. DDD feeds off of your resistance. Instead, accept that you are having a DDD moment. It’s OK to feel numb or detached. It’s not the end of the world. You can work your way out of it. With time, it will pass. Acceptance diffuses the energy of DDD.

- Positive Self-Talk: After accepting the fact that you are having a DDD moment, talk to yourself in a positive manner. “It’s going to be OK.”, “You are safe.”, “This isn’t going to last forever.”, “Stay calm.”, “This will be over soon.”,”There’s hope.”

6. Unusual or exaggerated beliefs about personal powers to understand the meanings or influence of events; illogical or “magical” thinking typical of childhood in an adult

What is magical thinking?

According to Legg and Raypole (2020), it refers to the idea that you can influence the outcome of specific events by doing something that has no bearing on the circumstances.

It’s pretty common in children. Remember holding your breath going through a tunnel? Or not stepping on sidewalk cracks for the sake of your mom’s back?

Magical thinking can persist into adulthood, too.

You’ve probably come to terms with the fact that monsters don’t live under the bed, but you might still check (or do a running jump into bed), just in case.

Generally speaking, there’s nothing wrong with following rituals or superstitions. Sometimes, though, magical thinking can be a sign of a mental health condition.

What about religion?

Some people consider religion a form of magical thinking. However, it’s important to consider the context of someone’s background when it comes to this debate. Sure, some people have beliefs that seem like magical thinking to those who don’t belong to the same culture or religion. To an atheist, for instance, prayer might seem like a form of magical thinking.

But magical thinking generally involves doing things you know — deep down — won’t affect the final outcome of something. Most religious people hold their beliefs as truths, so religion isn’t necessarily an example of magical thinking (Legg & Raypole, 2020).

However, uncontrollable and exaggerated magical thinking can be a symptom for mental health disorders, like obsessive-compulsive disorder, schizophrenia and anxiety disorder (Legg & Raypole, 2020).

7. Uncharacteristic, peculiar behaviour

What would be defined as a peculiar behaviour?

Picture this! Someone might walk halfway across the street, then turn around and walk back in the direction they just came from. Now, that is an odd thing to do.

As stated by a professor of Psychology and Marketing at the University of Texas (2016), without knowing much about it, you might come up with several possibilities:

- Perhaps they are absent-minded, so they were not paying attention to where they were going until they realized they should not have stepped into the street.

- They might have gotten into the crosswalk and then realized that they forgot to bring something with them and went hurrying back to their office to get it.

- Perhaps this person is about to go on a long journey and in their family it is good luck to cross half way across a street before going.

- It is possible that the action was driven by a reason that was related to the specific environment. Perhaps the sidewalk on the opposite side of the intersection was blocked.

What is the real definition of an odd behaviour of a person? You need to make the comparison with the previous normal behaviour of the person. What is normal for him or her?

8. Rapid or dramatic shifts in feelings or “mood swings”

According to Legg & Silver (2019), it’s normal to have days where you feel sad or days when you’re overjoyed. As long as your mood changes don’t interfere with your life to an extreme degree, they’re generally considered to be healthy. But if your behavior is unpredictable for a number of days or longer, it may be a sign of something more serious. You may feel grumpy one minute and happy the next. You may also have emotions that can cause damage to your life.

For example, you may:

- be so excitable that you find yourself unable to control urges to spend money, confront people, or engage in other uncontrollable or risky behaviors

- feel like you want to harm yourself or end your life

- be unable to visit friends, get enough sleep, go to work, or even get out of bed

If you’re experiencing severe shifts in mood, or mood changes that cause extreme disruption in typical behavior, you should talk to your doctor. They can help you determine the causes of your shifts in mood and help you find appropriate treatment. You may need professional therapy or medications to relieve these life-altering shifts in mood. Simple lifestyle changes may also help, too. Keeping a journal to record your significant shifts in mood might also help you determine the reasons you experience them. Look for patterns and try to avoid situations or activities that directly impact your mood. Sharing the mood journal with your doctor can also help with your diagnosis (Legg & Silver, 2019).

REFERENCES

Allgaier AK, Schiller Y, Schulte-Körne G. Wissens- und Einstellungsänderungen zu Depression im Jugendalter: Entwicklung und Evaluation einer Aufklärungsbroschüre. Kindheit und Entwicklung. 2011;20:247–255.

American Psychiatric Association (n.d.). Warning Signs of Major Mental Illnesses. Retrieved May 5, 2021, from http://www.socalpsych.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/APA-WarningSigns.pdf

Barzeva SA, Meeus WHJ, Oldehinkel AJ (2019). Social withdrawal in adolescence and early adulthood: Measurement issues, normative development, and distinct trajectories. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 47:865. DOI: 10.1007/s10802-018-0497-4

Bates, D. (2019, November 09). Anchoring yourself in reality. Retrieved May 05, 2021, from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/mental-health-nerd/201911/anchoring-yourself-in-reality

Biggers, A., & Nall, R. (2019, September 6). What Makes You Unable to Concentrate? Retrieved May 5, 2021, from https://www.healthline.com/health/unable-to-concentrate

Costello E, Egger H, Angold A. (2005). 10-year research update review: the epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: I. Methods and public health burden. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 44:972–986.

Goldsmith, B. (2021, March 03). A life without pleasure: The pain of anhedonia. Retrieved May 05, 2021, from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/emotional-fitness/202103/life-without-pleasure-the-pain-anhedonia

Hyde J, Mezulis A, Abramson L (2008). The ABCs of depression: Integrating affective, biological, and cognitive models to explain the emergence of the gender difference in depression. Psychol Rev. 115:291–313

Legg, T. J., & Silver, N. (2019, December 5). What Can Cause Rapid Shifts in Mood? Retrieved May 5, 2021, from https://www.healthline.com/health/rapid-mood-swings

Markman, A. (2016, November 21). How do people explain puzzling behaviors? Retrieved May 05, 2021, from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/ulterior-motives/201611/how-do-people-explain-puzzling-behaviors

Rubin KH, Coplan RJ, Bowker JC. (2009). Social withdrawal in childhood. In: Annual Review of Psychology. Vol. 60. Palo Alto: Annual Reviews; pp. 141-171.

Saitō T. (1998). Shaikaiteki hikikomori: Owaranaishishunk [Hikikomori: Adolescence without end]. Tokyo: PHP Kenkyuujo.

Saitō T. (2010). Hikikomori no hyouka shien ni kansuru gaidorain [Guideline on evaluation and support of hikikomori]. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour & Welfare.

Schulte-Körne, G. (2016, March 18). Mental health problems in a school setting in children and adolescents. Retrieved May 05, 2021, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4850518/#R21

Suwa M, Suzuki K. (2013). The phenomenon of “hikikomori” (social withdrawal) and the socio-cultural situation in Japan today. Journal of Psychopathology. 19:191-198

Responses