All Ages Are The Best Age To Be: An Interview with Dr. Jenni Ogden

Interested in the cross-section of neuropsychology and society, Dr. Jenni Ogden explores the recent flexibility that ideas of age and success have gained in this century in her article, “What’s the Best Age to Be?” Dr. Ogden holds a PhD in psychology, several postgraduate qualifications in clinical psychology and neuropsychology, and is an award-winning author of both fiction and non-fiction novels. An Emeritus Fellow of the Royal Society of New Zealand and the New Zealand Psychological Society, she has practiced as both a clinical psychologist and neuropsychologist and had written over 60 scientific journal articles. Her work was recognized by the International Neuropsychological Society in 2015 with a Distinguished Career Award. Her non-fiction books, Fractured Minds, and Trouble In Mind feature incredible stories of patients with a variety of neuropsychological disorders, while her fiction books such as A Drop in the Ocean features psychological and medical subthemes. Below she has shared her experience and insight as a neuropsychologist and her thoughts on age and success in this day and age, mainly how we can incorporate these ideas into our culture and personal lives for higher levels of engagement! Be sure to read her full article for more interesting, in-depth discussion, and to subscribe to her monthly e-newsletter and visit her author website and blog!

Interested in the cross-section of neuropsychology and society, Dr. Jenni Ogden explores the recent flexibility that ideas of age and success have gained in this century in her article, “What’s the Best Age to Be?” Dr. Ogden holds a PhD in psychology, several postgraduate qualifications in clinical psychology and neuropsychology, and is an award-winning author of both fiction and non-fiction novels. An Emeritus Fellow of the Royal Society of New Zealand and the New Zealand Psychological Society, she has practiced as both a clinical psychologist and neuropsychologist and had written over 60 scientific journal articles. Her work was recognized by the International Neuropsychological Society in 2015 with a Distinguished Career Award. Her non-fiction books, Fractured Minds, and Trouble In Mind feature incredible stories of patients with a variety of neuropsychological disorders, while her fiction books such as A Drop in the Ocean features psychological and medical subthemes. Below she has shared her experience and insight as a neuropsychologist and her thoughts on age and success in this day and age, mainly how we can incorporate these ideas into our culture and personal lives for higher levels of engagement! Be sure to read her full article for more interesting, in-depth discussion, and to subscribe to her monthly e-newsletter and visit her author website and blog!

Dr. Ogden, what is the field of neuroscience and how does it relate to psychology?

Neuroscience is a very broad field and one of the fastest growing research areas. It covers anything that includes the brain and nervous system, from studies of single neurons in the brain to studies of the efficacy of rehabilitation for people with brain damage. Human psychology is the study of the mind and behavior, and again covers a wide range of topics, from experimental studies of how we perceive color, how social in-groups and out-groups are formed, how young children develop cognitive and social skills, what causes depression, or psychosis, how young women cope with miscarriage or a broken relationship, to therapy with clients and families who are struggling with any of these and numerous other issues, from bed wetting, to relationship breakup, to drug addiction, to suicidal thoughts.

My own field, clinical neuropsychology, straddles neuroscience and psychology as it is concerned with the psychological aspects connected specifically with brain functioning and usually with brain impairment. From a research point of view it allows us to study the brain using psychological techniques. Training to be a clinical neuropsychologist involves training in psychology, and preferably in clinical psychology (as brain-damaged clients and their families will need your clinical psychology skills to help them cope), and training in neuroscience, including neuroanatomy, neuropathology and techniques for assessing neuropsychological disorders (cognitive tests and brain imaging techniques, for example.)

Why did you decide to study clinical psychology and neuropsychology in particular?

I wanted a career where I could combine working clinically with people with psychological and neuropsychological problems as well as carrying out research on how the mind works. I fell completely in love with neuropsychology when I took a Masters- level course in it, and became fascinated with how people with different types of brain damage think and behave, and how this can provide clues as to how the ‘normal’ brain works.

I wanted a career where I could combine working clinically with people with psychological and neuropsychological problems as well as carrying out research on how the mind works. I fell completely in love with neuropsychology when I took a Masters- level course in it, and became fascinated with how people with different types of brain damage think and behave, and how this can provide clues as to how the ‘normal’ brain works.

For my PhD I studied a very strange phenomenon called visual hemineglect, where a person with damage to one side of their brain (through stroke or tumor or head injury) ignores the side of space opposite to their brain lesion. These patients, especially those with damage to the right hemispheres of their brains, ignore people and objects appearing on their left side, draw only the right sides of pictures, and eat only the food on the right sides of their plate and then complain that they are hungry! My PhD included assessing for hemineglect over 100 brain damaged patients in an acute neurosurgery/neurology ward, and in the process I came across many other patients with fascinating neuropsychological disorders. As I was also a qualified clinical psychologist I found I could easily build a good rapport with my ‘patients’ and that helping them to understand what was happening to them and to cope better with it was as important as acquiring data about hemineglect for my research.

Later I went on to study and test ways to rehabilitate neglect at least for some of the patients. My life-time fascination with the ‘single-case study’ and what we can learn from a detailed understanding of one case came out of my PhD, and I have since published numerous research articles on a wide range of neuropsychological disorders, as well as published books for neuropsychology students and for the general reader on my favorite cases. My love of neuropsychology has even crept into my novels as I believe that is a way to increase general understanding of brain disorders and how they affect victims and families.

After obtaining your PhD, you did a postdoctoral research fellowship at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Can you speak a little about your experience working with the amnesiac HM, the man with no memory and the world’s most studied neurological case?

HM was a delightful person to work with; always willing to chat (even though he forgot who I was or what he’d said within seconds of saying it) and very easy to assess on all sorts of strange neuropsychological tests. He had a great sense of humor and we would often both be in fits of giggles, for example when I was asking him to copy my vocal expressions with a voice that was happy, sad, angry, disgusted etc. Although I was assessing him for a number of different research studies on his ability to mentally rotate objects, for example, and his ability to understand emotional facial expressions and voice tone, my main interest became understanding HM as a person who lived in a seven second time bubble. How did he cope with this? How did he understand it? I was one of the very few researchers to publish articles and chapters about these more personal aspects of ‘being HM’ or more generally, living with severe amnesia. My findings can be found in my books, “Fractured Minds” and “Trouble in Mind” as well as in some articles and many blog posts. When I was with HM I took two photos of him for my own ‘album’ which, after his death when he was in his eighties, turned out to be about the only photos of him in existence and are now used everywhere!

HM was a delightful person to work with; always willing to chat (even though he forgot who I was or what he’d said within seconds of saying it) and very easy to assess on all sorts of strange neuropsychological tests. He had a great sense of humor and we would often both be in fits of giggles, for example when I was asking him to copy my vocal expressions with a voice that was happy, sad, angry, disgusted etc. Although I was assessing him for a number of different research studies on his ability to mentally rotate objects, for example, and his ability to understand emotional facial expressions and voice tone, my main interest became understanding HM as a person who lived in a seven second time bubble. How did he cope with this? How did he understand it? I was one of the very few researchers to publish articles and chapters about these more personal aspects of ‘being HM’ or more generally, living with severe amnesia. My findings can be found in my books, “Fractured Minds” and “Trouble in Mind” as well as in some articles and many blog posts. When I was with HM I took two photos of him for my own ‘album’ which, after his death when he was in his eighties, turned out to be about the only photos of him in existence and are now used everywhere!

You taught clinical psychology and neuropsychology at the University of Auckland, New Zealand for 22 years and published 60 research papers on a wide range of neuropsychological disorders. What has a career in academia been like?

For me it was an enormous privilege to have a university career in an area I loved. I especially liked that it was never boring and the variety was enormous. I taught and supervised both undergraduate and postgraduate students and was the Director of the Postgraduate Doctorate in Clinical Psychology program; I was involved in a psychology clinic where I both saw clients and supervised clinical psychology students; I carried out many and varied research projects of my own (and supervised student projects) in the field of clinical neuropsychology, mostly in the hospital departments of Neurology and Neurosurgery, and I worked both clinically and within research projects with hundreds of amazing ‘brain-damaged’ patients and their families, who taught me a great deal about courage and resilience, as well as about human behavior and the brain. I also published books on neuropsychology, “Fractured Minds” and “Trouble in Mind” which have continued to sell well for many years.

What has been your greatest accomplishment in your career?

I have found that my perception of ‘accomplishment’ is a moving feat. When I got my PhD at the late age of 36, after four children, that was my greatest career achievement, but within a year that was in the past and I had new goals! I have been fortunate to receive a number of honors, including a Fellowship of the Royal Society of NZ, a Fellowship of the Psychological Society of NZ, and the Distinguished Career Award by the International Neuropsychological Society. Recently, since my ‘early’ retirement from my neuropsychology career and moving on to my new career as a novelist, my greatest accomplishment is having my first novel “A Drop in the Ocean” published in the US. It has won many awards and is about friendship and love and hard choices and marine turtle conservation, but it also has a neuropsychological subtheme! I love writing fiction and plan many more novels from now on. I now spend my writing time on a monthly e-newsletter on off-grid living, writing, and life generally (please do subscribe!), a monthly blog post, and reviewing other peoples’ books as well as writing my own.

I have found that my perception of ‘accomplishment’ is a moving feat. When I got my PhD at the late age of 36, after four children, that was my greatest career achievement, but within a year that was in the past and I had new goals! I have been fortunate to receive a number of honors, including a Fellowship of the Royal Society of NZ, a Fellowship of the Psychological Society of NZ, and the Distinguished Career Award by the International Neuropsychological Society. Recently, since my ‘early’ retirement from my neuropsychology career and moving on to my new career as a novelist, my greatest accomplishment is having my first novel “A Drop in the Ocean” published in the US. It has won many awards and is about friendship and love and hard choices and marine turtle conservation, but it also has a neuropsychological subtheme! I love writing fiction and plan many more novels from now on. I now spend my writing time on a monthly e-newsletter on off-grid living, writing, and life generally (please do subscribe!), a monthly blog post, and reviewing other peoples’ books as well as writing my own.

In your article, you write about how different skills peak at different ages; the relationship between skill sets and age seems to be more subjective than previously imagined. Does psychology research support this notion or does it actually suggest a particular best age to be?

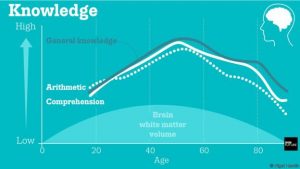

Sadly, our brains as well as our bodies do wear out, although some wear out faster than others! By staying healthy in mind and body we can stay ‘younger’ for longer, but in the end we will all get old! However, very old people can retain amazing fitness and cognitive agility as my Psychology Today blog post highlighted. This is likely partly genetic, partly good luck, and partly a consequence of those individuals remaining mentally and physically active. Over all, there are definitely cognitive functions that are sharper at younger ages, many in fact! But there are others that, like fine wine, improve—or at least don’t deteriorate—with age and experience. Amongst these are general knowledge, the ability to empathize and be less judgmental, and linguistic expression, such as well-structured and well-written fiction and non-fiction writing. And of most importance, in general, older people are happier and more content than younger adults. The take home message for every individual is to stay engaged, stay connected and find your passions. The more you use your brain, the longer it will continue to fire on most cylinders.

Sadly, our brains as well as our bodies do wear out, although some wear out faster than others! By staying healthy in mind and body we can stay ‘younger’ for longer, but in the end we will all get old! However, very old people can retain amazing fitness and cognitive agility as my Psychology Today blog post highlighted. This is likely partly genetic, partly good luck, and partly a consequence of those individuals remaining mentally and physically active. Over all, there are definitely cognitive functions that are sharper at younger ages, many in fact! But there are others that, like fine wine, improve—or at least don’t deteriorate—with age and experience. Amongst these are general knowledge, the ability to empathize and be less judgmental, and linguistic expression, such as well-structured and well-written fiction and non-fiction writing. And of most importance, in general, older people are happier and more content than younger adults. The take home message for every individual is to stay engaged, stay connected and find your passions. The more you use your brain, the longer it will continue to fire on most cylinders.

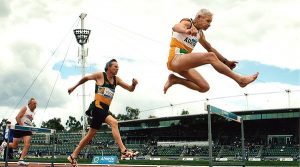

Do you know if New Zealand’s large festivals that celebrate success at older ages, The World Masters Games and the Auckland Writers’ Festival, are unique in their existence, or are there other similar events either in New Zealand or around the world?

The World Masters Games began in Toronto in 1985 and is held in different countries every four years. Writers’ festivals are also held around the world, although the format is different for different festivals. They can be small and intimate or large and international, and include workshops for writers as well as lectures, seminars and interviews by and with fiction and non-fiction writers, publishers, and journalists. Many include sessions with literary agents and editors as well. Some are specifically for writers, and others, like the Auckland Writers’ Festival, and the famous Hay-On-Wye Festival in Wales, are just as much for readers as for writers.

What might these more flexible ideas of age and success mean for society in this century? Can we incorporate them into today’s youth-centric culture?

Clearly a healthy and happy society is one where all age groups are included as equally essential and valued members. ‘Productivity’ is not the only criterion important for wellbeing, and indeed the definition of productivity is broad. Young people need mentors and teachers who can impart values as well as skills and experience, children thrive if they have the attention of grandparents, grandparents thrive if they have opportunities to spend quality time with their grandchildren, and if we forget or never learn our history, we will continue to repeat our mistakes. Older people need their children and grandchildren to explain how to use new technologies (like the TV remote!), to lead the way in the invention of new technologies that will increase sustainable living, reduce climate warming, and to do the heavy lifting. World peace needs everyone to cooperate: age does not correlate with the values and wisdom and insight and foresight and knowledge that peace requires.

T he key to enjoying all age groups whatever age we ourselves are, is to make an effort to find out what interests others, to listen—really listen— to them, to keep in mind our own tendency to age, or to remember that we were also so very young not so very long ago. The human life span is an infinitesimally small blip in time, and it is wasteful to ignore any portion of it.

he key to enjoying all age groups whatever age we ourselves are, is to make an effort to find out what interests others, to listen—really listen— to them, to keep in mind our own tendency to age, or to remember that we were also so very young not so very long ago. The human life span is an infinitesimally small blip in time, and it is wasteful to ignore any portion of it.

If you could give one piece of advice to Millennials and future generations, what would it be?

Conservation. If we—whatever age we are—do not immediately, persistently and consistently make efforts to minimize our carbon footprint, reduce climate warming, reduce population growth, and strive to live more sustainably, our children and grandchildren will not have a world that is worth living in.

Thank you Dr. Ogden for sharing your insight and experience with us!

For more on Dr. Ogden, watch her Ted-style talk at the Mind & Its Potential conference on H.M. and other cases of listen to an interview on the Australian National Radio program, All In The Mind, on her patients, and check out her Off-grid life story with pictures!

To keep up with Dr. Ogden, like and follow her social media accounts: author Facebook page, personal Facebook page, LinkedIn, Twitter, and Goodreads.

Responses