Why Idealism Never Gets You Past the First Stage of Relationships

The first time I watched 500 Days of Summer, I couldn’t help but hope that somewhere down the road, Summer would finally be able to meet Tom in the middle. Even though it’s clearly stated from the very beginning that it’s not a love story, Tom is a romantic. He always felt like he could never be complete without finding the one. Although he studied architecture, Tom works as a greeting card writer instead. He meets Summer at work when she’s hired as his boss’s assistant and the two become friends.

Summer is the opposite of Tom —a hardcore realist who doesn’t believe in love. But Tom becomes intrigued with her all the more because of that (and, of course, because she also likes The Smiths). Throughout the film, we see Summer from Tom’s point of view. As a result, we understand why he’s so crazy about her, making it easy for us to sympathize with him when she breaks his heart in the end. But after watching the film a few more times, I stopped feeling bad for Tom and his idealistic ways. I say this because even though he insisted on playing the victim, he, in more ways than one, brought the heartache upon himself.

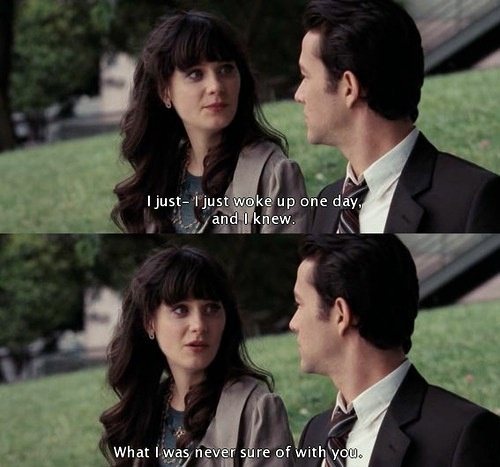

Summer never wanted anything serious with Tom. She told him from the very beginning that she was only interested in being friends with him. She even asked him if that was okay with him, and he said yes. But of course it only made him try all the harder to win her over. To be fair, though, the lines were blurred in the middle of the story-line when Tom felt as though they had something special that could potentially turn into more than their so-called friendship. So, he asked her, “What are we doing? What are we?” Summer smiled, threw her head back, and said, “I don’t know.”

The first relationship stage is the romance stage, otherwise known as the drug addiction stage. Tom, being a natural romantic, finds it to be his natural habitat because that’s how he grew up perceiving the world in general. In the first stage, people feel like they’re high and nothing hurts, because they’re too busy focusing on the good, leaving the bad out. Couples can stay in the first stage ranging from 2 months to 2 years, depending on how long the love chemicals released in their brain last. Most books and films in our culture depict ultimate love in this manner when, in reality, it’s just the beginning. And the real work of relationships hasn’t set in yet.

Tom is convinced he loves everything about Summer. He completely ignores the red flags she throws out at him continuously when she doesn’t want to give them a label other than “just friends.” It’s clear that they make a close pair of friends when she opens up to him about the dreams she has and states that she’s never confided in someone about the realism and loneliness she’d felt all her life. She may be a cynical and tough-minded woman, but at the end of the day, she has emotions, too. And she felt some confusion towards Tom, as a result. Tom can hate her all he wants in the initial stage of their breakup.

But as someone watching the film, I can say from my observations that Summer wants love just like anyone else. She cried after watching a scene at the movie theater with a wedding couple, most likely yearning for that same exact dream. I think it was the more humanized version of Summer we see in the entire movie. It makes it easier to forgive (at least that was the case for me) the occasional blurred actions she threw at Tom that made him experience the spiraling depression when she finally ended it between them once and for all.

Tom is such an idealist that he only let his dreams be dreams and nothing more. He doubted the talents he possessed as a potential architect and wasn’t willing to go through the sacrifices, hard work, and failures of becoming one —at least, not until Summer instilled a wake up call in him after leaving him. He just selfishly wants the good, but he isn’t willing to work through the harsh realities just to get there.

When Tom shows Summer his favorite spot for the first time, he talks about the buildings with such passion and vigor, as if the buildings are people he’s known all his life. When Summer points to something in the far distance and asks him what it is, Tom laughs and says that it’s a parking lot and then says, “There’s a lot of beautiful stuff here, too, though.” He says that he wishes people would notice this spot more and find the same things he finds to be beautiful.

It’s strange, though, isn’t it? Tom is an idealist, and yet he doesn’t find the parking lots to be beautiful when he just regards them as an ordinary part of society’s functions. People park their cars in lots all the time without thinking twice about the value they hold —there’s nothing romantic about them. I know this myself. Smoking my very first cigarette when I was 20 in a parking lot at midnight, I thought it would perhaps shed light on something I was missing out on all this time. But it didn’t. I found it so completely useless. I’m just lucky that I never got addicted, not even after my second cigarette.

Tom is lucky, too, in a lot of ways. He’s lucky that he was able to eventually separate himself from his idealistic views that only consumed him in the end making him so completely lovesick. Tom’s friend Paul is my favorite character. When trying to explain what love is at one point of the film, he talks about Robin, his lover whom he’s known since elementary school. He says that, ideally, the woman of his dreams would be more bodacious, have a larger rack, and be more into sports, but he’s not disillusioned the way Tom was. He said Robin is better than his dream girl because she’s actually real. Paul’s take on love is refreshing and gives the viewer a break from Tom’s overwhelming ideals that only ruined him in the end.

But ultimately, Tom still had the guts to believe in love when he meets Autumn. The ending, however, remains a mystery. We don’t know if Autumn is, in fact, the one for Tom. But that’s exactly the point. Tom confessed to Summer when they were making up from an argument that he needs consistency and the reassurance that the next morning when she wakes up, she won’t feel any different. She said that she can’t give that to him —no one can. When you have such a strong set of ideals and beliefs, you place yourself in such a high place that only makes you see things from a distance. You grow comfortable seeing those things from that distance just like how Tom sees buildings far away from his favorite spot in the city —always dreaming, but not actually designing the buildings himself up close and personal.

There’s no growth or self-actualizing in that. That’s why Tom experienced so much painful confusion when it felt like the breakup happened out of nowhere. He never pulled himself past the 1st relationship stage. He never turned to the next page. That’s pretty tragic. Summer, however, gave him closure in the end when they meet at his favorite spot once again. He’s lucky. Oftentimes in real life, not many people actually get the closure they want from a horrible breakup. And yet, we force ourselves to trudge along anyway, because there’s no other way out of misery.

It’s healthy to have ideals and dreams. But to live inside of them forever —you’d only be preventing yourself from reaching your true potential. Operating on the ground of reality to make them come true, however, is where the actual magic exists. You can’t romanticize struggle. But you can look forward to the mornings you realize you’re doing something you’re passionate about and loving someone worthwhile.

References:

Muzik, B. (2016). The Five Stages of Relationships: Which Relationship Stage Is Yours At?

Webb, M. (Director). (2009). 500 Days of Summer [Video file]. United States: Fox Searchlight Pictures.

Edited by Viveca Shearin

Responses