A Survival Guide: An Interview with Christopher Bergland

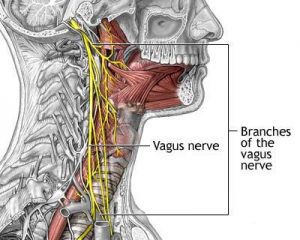

The following is Mr. Bergland’s list of vagal maneuvers detailed in his Psychology Today blogs.

The Vagus Nerve Survival Guide by Christopher Bergland

- Diaphragmatic Breathing Exercises

- Tonic Levels of Daily Physical Activity

- Face-to-Face Social Connectedness

- Narrative Expressive Journaling

- Gutsy Third Person Self-Talk

- Sense of Awe to Promote Small Self

- Upward Spiral via Loving-Kindness Meditation

- Superfluidity and Secular Transcendent Ecstasy

- Volunteering and Altruistic Generativity

Just like any other human, you may find it difficult to turn these into habits or you may fail to practice what you preach. To show us how to deal with these, let’s look at how Mr. Bergland applied these vagal maneuvers to his life, the obstacles he faced, and how he managed to get back on track.

Christopher Bergland is a world-class endurance athlete, coach, author, political activist, and father. He is a three-time champion in Triple Ironman and he holds a Guinness World Record for running. He is the author of The Athlete’s Way in Psychology Today.

You wrote several blogs about the vagus nerve, can you tell us how did it capture your interest?

My interest in the vagus nerve began as a young tennis player being coached by father (who was a neurosurgeon). My dad taught me how to use “vagal maneuvers” (such as deep, slow breathing) to stay calm, cool and collected while serving a tennis ball during stressful matches. Because my father had to maintain grace under pressure during life-or-death brain operations, he had fine-tuned a variety of techniques to keep his nervous system regulated by engaging his vagus nerve. He shared these methods with me as a tool that I could adapt to improve my psychophysiology during sports competitions.

The most basic and valuable vagus lesson and story my father shared with me was that in 1921 a Nobel Prize-winning German physiologist, Otto Loewi, discovered that when someone takes a deep breath and exhales slowly that the vagus nerve squirts the inhibitory neurotransmitter acetylcholine directly onto the heart. This instantaneously counters the panicky fight-or-flight response of the sympathetic branch of the nervous system. Loewi originally called acetylcholine “vagusstuff” (German for “vagus substance”) So, my father would say to me on the tennis court in a coaching voice, “Chris, remember to take a deep breath and exhale slowly to squirt some vagusstuff onto your heart and calm your nerves as you bounce the ball three times, before tossing your serve.” (I still adhere to this ritual anytime I play tennis.)

You also wrote about the shared powers of vagus nerve and mindfulness meditation. Some doubt the real benefits of the latter. What are some doubts or oppositions you have faced in advocating the powers of vagus nerve?

A few weeks ago, when I was totally immersed in researching and writing my recent nine-part vagus nerve series, my mom called one day to check in and find out what I was up to. She was very interested and enthusiastic as I explained the power of vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) to reduce systemic inflammation, treat depression, addiction. I told her about how the holistic vagal maneuvers I’d curated for the series could improve prosocial behaviors such as tending-and-befriending, reduce anxiety, anger, aggression, egocentric bias, etc. And, she thought it was all really interesting and valuable information.

But then, I mentioned the words “mindfulness meditation.” My mom interrupted me abruptly and said in a disappointed and kind of harsh tone. “Oh, no. Chris, please don’t get too woo-woo or new agey about the vagus nerve. Can’t you keep it strictly science-based? You know all about the backlash of people making dubious claims about the benefits of meditation and mindfulness…and that whole topic has been overplayed lately.” My mom is also a public health advocate, and a real pragmatist when it comes to evidence-based advice.

I chuckled about her intense knee-jerk reaction. We both laughed and agreed that the abundance of wishy-washy ‘mindfulness’ advice was oftentimes annoying. But, then I explained to her that in this situation the main type of meditation used to engage the vagus nerve was called “loving-kindness meditation” (LKM), which has very clear-cut parameters and is systematic. I also let mom know that one of the world-renowned leaders and medical experts on the benefits of health vagal tone, Barbara Fredrickson, had conducted extensive pioneering research on the link between an upward spiral of well-being, prosocial behaviors, loving-kindness meditation, and the vagus nerve.

Then, I explained the four-step LKM process to my mom (which is something that I would do for anyone who seemed doubtful about the benefits of using a meditative practice to engage the vagus nerve) and she became less skeptical because the advice was cut-and-dry. To practice LKM, all you need to do is systematically send empathy, compassion, and magnanimous thoughts to four categories of people (1) Friends, family, and loved ones. (2) Strangers around the world and locally who are suffering. (3) Someone who has hurt, betrayed, or disappointed you. (4) Forgive yourself for any negativity or harm you’ve caused and make a vow to stop holding grudges against yourself.

Where are studies at the moment and where do you anticipate findings going in the next year or so?

Kevin J. Tracey is a trailblazer on the forefront of vagus nerve research. He was also the first to identify “The Inflammatory Reflex” which found that acetylcholine (vagusstuff) plays a central role in reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines that are linked to a wide range of chronic diseases and premature death. Tracey is waiting for FDA approval to use VNS to treat rheumatoid arthritis and severe inflammation. Hopefully, these approvals will come in the next year or so.

Given the number of studies about the benefits of stimulating the vagus nerve, in what kind of policies or practices do you want them to be applied? And what changes do you hope to see when applied?

What I love about giving actionable advice that focuses on the vagus nerve is that it is a singular “self-help” remedy that addresses a triad of public health epidemics which include: anxiety, anger, and inflammation. Also, because most people don’t even know they have a vagus nerve—or how extensively it wanders through their body—once they make a visual connection to their own vagus nerve it makes the science-based advice tangible and easy to visualize within their own nervous system.

Also, there is so much talk about fight-or-flight mechanisms, but so little discussion about how to counter this aspect of the autonomic nervous system by engaging the “tending-and-befriending” parasympathetic vagus response. At a time when the headlines are filled with hateful rhetoric, Tweetstorms, and political attempts to destabilize everyone’s sense of security. Statistics show that bigotry, xenophobia, and hate crimes are also on the rise across the United States. Teaching people how to perform individual vagal maneuvers that fit their lifestyle has the power to improve our overall civility, increase tolerance, and benefit society as a whole.

I know it’s idealistic but, my hope is that by educating and inspiring individuals (who learn various ways to engage the vagus nerve by reading articles like this) to make a small effort to improve his or her vagal tone could kickstart a collective upward spiral of more civility, empathy, and warm heartedness towards one another. I would love to see teachers, parents, and other thought leaders spreading the word about how harnessing your vagus nerve can be an antidote for the society-wide epidemic of anxiety, anger, and aggression that has swept our nation.

Moving to your personal experience, do you mind telling us what vagal maneuver do you use most often and how did it change your life?

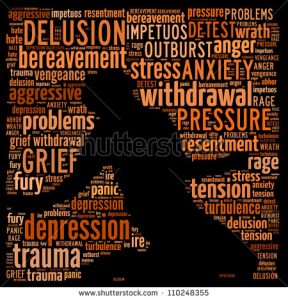

Daily physical activity at a “tonic level” is the vagal maneuver I use most regularly. And it has definitely transformed my life. As a teenager, I struggled with the triple whammy of free floating anxiety, depression, and unbridled rage towards a dean I had in boarding school who publicly shamed and humiliated me to the point of suicidal ideation at a vulnerable period in my life.

Luckily, I discovered the joy and neurobiological power of running to reshape my brain and nervous system when I was seventeen. Running turned my life around. I went from being a nervous wreck who felt powerless, self-destructive and hated myself to feeling self-compassion and inner calmness based on the fact that I was comfortable in my own skin, felt in control of my day-to-day life, and wholeheartedly believed I was the ruler of my destiny.

After graduating from college, I started competing in marathons and Ironman triathlons. These endurance sports tend to have a high rate of burnout due to overtraining and injury. Fortunately, I had a coach who was an exercise physiology geek fastidiously monitored my Heart Rate Variability (HRV) regularly to make sure I wasn’t overtraining. HRV is way to make sure that you maintain a robust vagal tone index. High VT means that your parasympathetic system is keeping your “fight-or-flight” mechanism in check and that you are in a sweet spot of balanced homeostasis within your “milieu intérieur.”

Although physical activity is one of the best ways to engage and stimulate your vagus nerve, too much exercise can backfire and lead to a hyperactive “fight-or-flight” sympathetic nervous response and chronically high HPA-axis, which is a marker for stress hormones such as cortisol. The trick with using aerobic exercise as a vagal maneuver is to find a level of exertion and intensity that feels good to you and to make sure that exercise doesn’t feel like a sufferfest by working out at a “tonic level.”

In your final entry of the vagus nerve series, you said that it was a call “to make a commitment to consciously seek daily lifestyle choices that keep your vagus nerve active and engaged.” We know that making something a habit takes time. Is there a time when you failed on this commitment? How did you deal with it?

On the eve of the 2016 Presidential election, I stayed up until 3AM watching the results come in. When it became clear that Hillary Clinton would lose the electoral college, I began to have a psychophysiological fear-based meltdown. I felt sick to my stomach and was physically trembling. My vagus nerve had become untethered and my fight-flight-freeze impulses were running wild. The uncertainty about my own future as an openly gay person along with the safety and well-being of other members of my LGBTQ community exacerbated my gut-wrenching visceral panicky response when I realized that the Trump-Pence ticket had won the election.

I woke up the next morning feeling hopeless and demoralized. Instead of rallying myself to be proactive or stick with “a commitment to consciously seek daily lifestyle choices that keep your vagus nerve active and engaged”. I curled up in the fetal position and did absolutely nothing. I basically spent the next few weeks completely paralyzed. I stayed locked in this “freeze” mode (which is directly tied to a maladaptive parasympathetic vagus response for a few weeks).

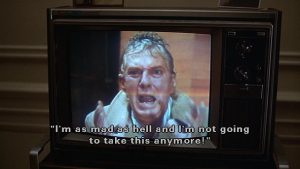

But then, my fear turned to uncontrollable rage. I had so much anger and hostility oozing from my pores that it was eating me up inside. Every time I turned on the cable news, my blood would start to boil. I’d find myself screaming at the television, “I’m mad as hell and I can’t take it anymore!!” (like Howard Beale in the movie Network). It had to stop.

As New Year’s Eve of 2017 approached, I made a resolution to snap out of it and to identify a way to become part of the solution and not the problem. I realized that starting with myself, I needed to recommit to making a daily effort to maintain robust vagal tone as a central way to cope with my anger and anxiety.

Additionally, because of my expertise as a science-based writer with a widely-read platform as a public health advocate, I decided to put together the Psychology Today “Vagus Nerve Survival Guide” series as a tool for other people who might also be struggling to cope with their own anxiety and uncertainty about the future.

I also wanted to pour my heart into something that might help break the vicious “us” against “them” cycle of identity politics and to spread a message of common unity that was founded in the universality of our neurobiology as human beings. Taken together all of these factors inspired me to take action and to make a commitment to practice what I was preaching.

What is your advice to ensure commitment to keep our vagus nerve active and engaged?

Being able to identify the tell-tale signs that your vagus nerve is NOT actively engaged–such as when you experience fight-or-flight responses marked by increased heart rate, rapid breathing, or a general feeling anger, hostility, or anxiety–is probably the most effective way to remind yourself to practice a vagal maneuver right then and there. And to stick with prophylactic habits to make these negative responses less likely to occur in the future.

Because most of us will undoubtedly experience some type of full-throttled sympathetic nervous response that makes us anxious, angry, or stressed out during the week, the best time to recommit to doing a vagus nerve activity is when you feel these unbridled emotions taking over. Luckily, taking a few slow, deep diaphragmatic breaths with a long exhale is a quick and easy way to instantly engage the “tending-and-befriending” mechanisms of your parasympathetic vagus system and increase prosocial behaviors just about anytime and anywhere.

Of course, not all problems can be solved by vagal maneuvers but they help stop some problems from escalating and suggest ways to spread kindness. Even experts like Mr. Bergland face the same circumstances that you do like nerve-wracking activities, being outraged or humiliated, and failing commitments. And just like him, hopefully, you can also get back on track, spread civility, empathy, and warm heartedness along the way, or as Gandhi said, be the change you want to see in this world.

Responses