The Stanford Prison Experiment & The Psychology of Evil

Have you ever wondered why people are the way they are? What determines a person’s nature, and what could make someone evil or good?

Philosophers, dramatists, and theologians have wrestled with these big questions for as long as man has been able to ponder them. And in this modern day and age, the search for answers continues to be carried out by psychologists and social scientists alike. But have you ever heard of one very notable psychologist who asked himself these very same questions and got more than he bargained for?

For many, Philip Zimbardo is largely known as the man behind “the psychological experiment that shocked the world” — the infamous 1971 Stanford Prison Experiment. More than 30 years after it ended, however, Zimbardo has since then gone on to set the record straight about what really happened and what it all means in what he calls “the psychology of evil.” But first…

A Brief History

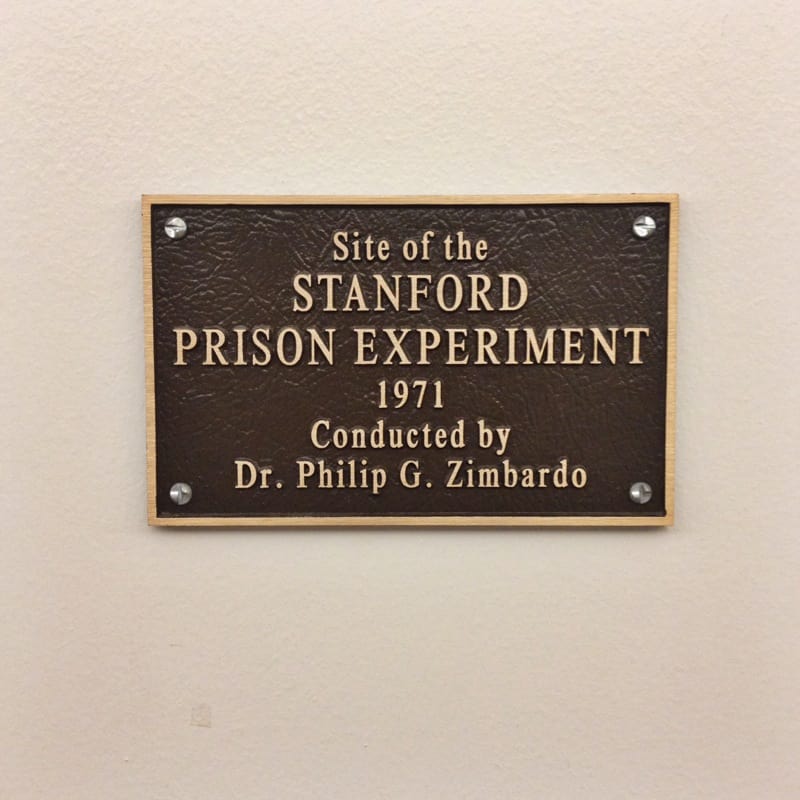

In August of 1971, Philip Zimbardo, a psychology professor at Stanford University, received funding from the U.S. Office of Naval Research to study the psychological effects of becoming a prisoner or prison guard.

Thus, he and his research team selected over 24 healthy, intelligent, middle-class male college students from the U.S. and Canada who happened to be in the Stanford area to participate. Once they agreed, a simple coin toss would then determine whether they would play the role of a prisoner or prison guard for the two weeks they would be studied.

Zimbardo and his team turned the basement of Stanford’s Psychology Department building into a makeshift prison, closing off the corridors, boarding up the windows, and replacing the doors with steel bars. At one end of the “prison” hall was a videotape recorder and an intercom system was secretly installed inside every cell to monitor “prisoners” conversations.

The questions Zimbardo posed were “What happens when you put good people in an evil place? Does humanity win over evil, or does evil triumph?” Well, his study seemed to support the latter hypothesis. Because after only 6 days, the experiment was terminated due to the alarming indignities and inhumane treatment the “guards” had been inflicting on the “prisoners.”

“Prisoners” were repeatedly beaten, humiliated, physically and emotionally harrassed, sometimes even for no good reason. In fact, after only 2 days, the “prisoners” staged a rebellion against the “guards.” Within the first 4 days, 3 “prisoners” had become so traumatized that they were released. Many “guards” quickly became cruel and tyrannical, while most “prisoners” became depressed and disoriented.

Many were understandably outraged by this, and the experiment quickly came under fire for its unethical practices (enabling the abuse of participants and illegally recording them, just to name a few). Still, in spite of all of this, Zimbardo insists that the Stanford Prison Experiment’s greatest and most lasting legacy is not the greater care psychologists have since then put into examining and enacting the ethical grounds of their studies, but what it teaches us about humanity and its boundless capacity for both good and evil.

The Lucifer Effect

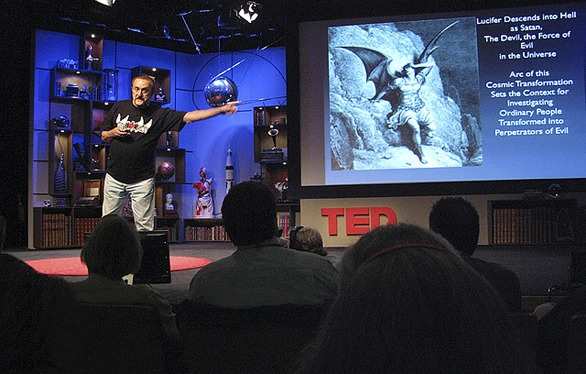

“Evil”, Zimbardo said, “is simply the exercise of power.” In his 2008 Ted Talk, he recounts the events of his infamous experiment as a way to explain the concept of The Lucifer Effect, saying that it is “the negatives that people can become and not what they are.”

Because his experiment showed that, for better or for worse, people will readily conform to the social roles they are expected to play, Zimbardo believes that good and evil lives within every one of us, and that the barrier between the two is permeable. It is only the situation that evokes one over the other, something he calls the Lucifer Effect and the Hero Effect.

“And so what we’re interested in is, what are the external factors around the individual — the bad barrel, not the bad apples?…If you want to change a person, you’ve got to change the situation. If you want to change the situation, you’ve got to know where the power is, in the system.”

The Hero Effect

But of course, just as how good people can turn evil in the wrong situations, the opposite can also be true. That the right conditions can make unlikely heroes out of anyone, and that we don’t always have to be victims of our own circumstances. To quote Zimbardo once again, “Heroism is the antidote to evil…(And we must) promote the heroic imagination, especially in our kids, in our educational system. We want kids to think, I’m the hero in waiting, waiting for the right situation to come along, and I will act heroically.”

What Zimbardo is proposing is nothing new. In fact, it’s a basic premise of social psychology known as “the power of the situation.” According to the American Psychological Association, “the power of the situation” posits that our thoughts, actions, and emotions are substantially influenced by social settings. What is relatively new, however, is his application of this concept to the way we think about good and evil in human nature.

In fact, Zimbardo even founded a non-profit research and education organization called the Heroic Imagination Project, which is dedicated to “designing innovative strategies by combining psychological research, intervention education and social activism to create everyday heroes equipped to solve local and global problems.” Their tagline? “We believe ordinary people can do extraordinary things. We train everyday heroes.”

Becoming An Everyday Hero

So, how do you become more heroic in your everyday life, you ask? Well, according to Zimbardo and the research he’s inspired, there’s power in picturing oneself asa “hero in waiting” and using our “heroic imagination.” Because the more we mentally prepare ourselves to intervene in challenging but mundane situations — like standing up to a bully or helping a stranger — the easier it becomes for us to tap into our innate potential for bravery, positivity, and altruism.

Other ways we can cultivate our heroic imagination include simple exercises such as: asking ourselves who we think of as our heroes; determining what characteristics they all have in common and trying to model their behaviors; looking for opportunities to be a little more heroic in our everyday lives; and challenging ourselves to be the first person to act in difficult situations. Because in the end, “the opposite of a hero is not a villain, but a bystander” (The Heroic Imagination Project, 2021).

So, are you ready to unlock your heroic imagination today? What are some ways you can be a little more heroic in your everyday life?

References:

- TEDx Talks [TEDxTalks]. (2008). The Psychology of Evil | Philip Zimbardo | https://www.ted.com/talks/philip_zimbardo_the_psychology_of_evil?language=en

- Zimbardo, P. (2011). The Lucifer effect: How good people turn evil. Random House.

- American Psychological Association (2022). APA Dictionary of Psychology. Retrieved from https://dictionary.apa.org/power-of-the-situation

- The Heroic Imagination Project (2021). Helping Kids Become Heroes. Retrieved from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/601c17649af0ad39b22c0901/t/60bea9218bb48d784b0568e6/1623107879814/HIP+Lesson+Plan+Teaching+Kids+to+Be+Heroes+2021.pdf

Responses