Motivating Those Who Are Afraid of Failure: An Interview with Dr. Adam Price

Dr. Adam Price is a clinical psychologist who, according to his twitter bio , is trying to find a cure for laziness. He has 20 years of experience working with children, teens, and families, is an expert in learning disabilities and ADHD, and specializes in working with unmotivated teens. His recently published book, “He’s Not Lazy” is an ideal read for parents looking for ways to help their unmotivated sons, and a fascinating glance into why it’s so difficult to grow up – from a teenage boy’s point of view. You can find out more about his book here and be sure to check out his blog for more insight into this topic and others.

Dr. Adam Price is a clinical psychologist who, according to his twitter bio , is trying to find a cure for laziness. He has 20 years of experience working with children, teens, and families, is an expert in learning disabilities and ADHD, and specializes in working with unmotivated teens. His recently published book, “He’s Not Lazy” is an ideal read for parents looking for ways to help their unmotivated sons, and a fascinating glance into why it’s so difficult to grow up – from a teenage boy’s point of view. You can find out more about his book here and be sure to check out his blog for more insight into this topic and others.

Dr. Price, what drew you to the field of child psychology?

That is a funny story. Most kids wanted to grow up to be fireman, policemen or baseball players. I wanted to be those things too, but I also wanted to be a psychologist. In kindergarten, I set up an “office” in my closet and had my friend draw pictures, because that’s what I thought psychologists did. I think it had something to do with the fact that my mother was a clinical psychologist!

What has been your primary focus as a professional in the field?

I have been fortunate to do a lot of things as a psychologist, but my focus has always been with teens and young adults. Teenagers are so much fun to work with because their minds are exploding with new insights about the world around them. Young adults, on the other hand, come to therapy with many questions about the kind of life they hope to lead. It is very rewarding to help them find answers to these questions.

In your book “He’s Not Lazy”, you paint a picture of the unmotivated teen boy and his parents who believe they have exhausted all possible options when it comes to helping their son. Could you explain the struggles teen boys are facing in today’s world?

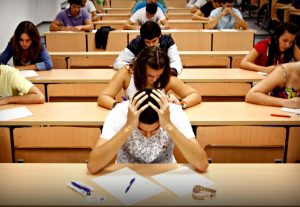

The teens I see want to do better in school, but are often scared to try. They are afraid because the demands placed on them have grown exponentially in the past twenty five years. According to The Nation’s Report card published by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) the average GPA increased from 2.68 in 1990 to 3.0 in 2009. High School graduates in 2009 also took three more credits (the equivalent of 420 additional class room hours) than their counterparts did in 1990. However, teenage brains are not maturing any faster.

There is also a perception that it is harder to get into college. That is really not true, but selective colleges are certainly more in demand. Part of this is cost driven—if a BMW and a Ford Escort both cost $60,000 why wouldn’t you want the BMW. Of course this analogy is only about the perceived status an Ivy League diploma brings; it falls short when you consider the overall college experience.

And finally, boys are afraid to fail. Being perfect has become the new average. Parents are worried to death that if their offspring do not achieve excellence now, they will fail at life so they do everything they can to prop their kids up, or drag them along. As a result, boys (and girls) don’t know how to deal with failure and adversity.

A key aspect in improving motivation is increased autonomy and independence. Would you say today’s parents are helping or hindering their children in this?

Parents are definitely hindering their kids from achieving autonomy and here is why. First of all, the helicopter parent does too much for their child and takes on the responsibility of their child’s success as if it were their own. But more importantly, autonomy is not the freedom to do whatever you want. Autonomy must come with accountability. In other words, it means having the freedom to make a decision and then to live with the consequences of that choice. This is crucial to learning how to make better decisions. However, the parents I see let their kids do what they want, but do not hold them accountable for the consequences of their actions.

Parents are definitely hindering their kids from achieving autonomy and here is why. First of all, the helicopter parent does too much for their child and takes on the responsibility of their child’s success as if it were their own. But more importantly, autonomy is not the freedom to do whatever you want. Autonomy must come with accountability. In other words, it means having the freedom to make a decision and then to live with the consequences of that choice. This is crucial to learning how to make better decisions. However, the parents I see let their kids do what they want, but do not hold them accountable for the consequences of their actions.

You suggest a strategic plan for parents who want to improve their son’s motivation and hopefully his behavior and performance in school. This is primarily to support executive functioning. What are these executive functions and why is it here that a parent should focus?

Any planning we human beings do involves the pre-frontal cortex of the brain. That section, right above your eyebrows, is the seat of what psychologists call the executive functions. Most people think of them as related to planning and organization, and while that is true, it’s a little more complicated. I devote a whole chapter to this topic in the book. What parents and teachers need to understand is that during the teenage years the pre-frontal cortex is going through a big growth spurt. It’s actually not fully developed until age 26. And although it is possible to support these functions in students, they really have to develop on their own.

In the beginning of the book you mention the need for a professionally successful parent having to undertake a paradigm shift when realizing his relationship with his son is more important than equating his son’s success with better academic performance. This almost seems like an extreme rewiring of one’s brain; are your patients and their parents typically successful in executing this shift?

I don’t think it is that extreme, but it does take some work. That is why I wrote the book. I truly believe that parents need to be given permission not to worry so much so that they can re-connect with the joys of raising a teenager. Once they do, they find that their kids are not only doing just fine, but are actually able to find their own internal motivation to succeed. I love when, at the end of one of my talks an anxious parent asks a question about their kid, and I get to tell them they don’t have to worry. You can feel the tension leave not just that parent, but everyone in the room. I have worked with many parents who were able to become their teens’ ally instead of their adversary. They did so by becoming better listeners, avoiding power struggles, and by employing empathy.

I don’t think it is that extreme, but it does take some work. That is why I wrote the book. I truly believe that parents need to be given permission not to worry so much so that they can re-connect with the joys of raising a teenager. Once they do, they find that their kids are not only doing just fine, but are actually able to find their own internal motivation to succeed. I love when, at the end of one of my talks an anxious parent asks a question about their kid, and I get to tell them they don’t have to worry. You can feel the tension leave not just that parent, but everyone in the room. I have worked with many parents who were able to become their teens’ ally instead of their adversary. They did so by becoming better listeners, avoiding power struggles, and by employing empathy.

You debunk a lot of myths throughout the book, many of which took me by surprise! As someone in the field for over two decades, do you find yourself also learning or re-learning previously engrained “truths”?

In some ways the field of psychology has changed dramatically and in other ways it’s stayed very much the same. While many of Freud’s ideas have been debunked, I think the premise of his argument is still quite valid. Newer treatments like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Dialectic Behavior Therapy have offered real relief for some problems, but there is still no one size fits all therapy. What never seems to change is the depth of human suffering- both self-inflicted and the kind we wreak on others. At the same time, I am also keenly aware of the need for compassion. It is the only response to this suffering that makes sense, and we all have the capacity to offer it. No matter the school of thought, a therapist’s most effective tool is very simple: to listen without judgment in order to really hear what our patients need to tell us.

Child psychology must be an incredibly fulfilling profession. What would you say was your greatest accomplishment throughout your career?

I know it sounds corny, but every time I connect with a young person and engage them in therapy I feel a great sense of accomplishment.

If you could give today’s millennials and the many generations to follow a single piece of advice, what would it be?

That is easy: don’t be afraid to take a risk, make a mistake, or even to fail. Failure is not about doing something wrong, it’s about learning to do it right. Oh, and do your own laundry and clean your room. (I guess that is three pieces of advice).

Interesting interview, Marta! I especially agree when Dr. Price touches upon the fact that there truly is no one size fits all in regards to approaching therapy. When he mentions the complexity of the human depth of suffering and the immense need for compassion, I think it certainly sheds light on what still needs to be dished out in order to achieve a sense of peace. Moreover, I think it’s just a willingness to try to understand, which is where learning to become a child’s ally instead of his/her adversary comes into play. Relinquishing power struggles is something I think is vital for healthy parenting, and I’m glad Dr. Price revealed that important piece of information.

Thanks for reading Catherine. I agree, relinquishing power struggles is really the key to any healthy relationship, including between parents and children.